Chapter 3: The Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF)

From the BOLD Response to the HRF

In the previous chapter you read about a number of assumptions that are made about what the BOLD signal represents; another assumption we make is what the BOLD response looks like. This is important not only for modeling the link between neural activity and blood flow, and from there to the observed signal, but for how we define a model to test which brain regions show a significant change in their BOLD response to a given stimulus.

In the 1990’s, empirical studies of the BOLD signal demonstrated that, after a stimulus was presented to the subject, any part of the brain responsive to that stimulus - say, the visual cortex in response to a visual stimulus - showed an increase in BOLD signal. The BOLD signal also appeared to follow a consistent shape, peaking around six seconds and then falling back to baseline over the next several seconds. This shape can be modeled with a mathematical function called a Gamma Distribution. When the Gamma Distribution is created with parameters to best fit the BOLD response observed by the majority of empirical studies, we refer to it as the canonical Hemodynamic Response Function, or HRF.

When applied to fMRI data, the Gamma Distribution is called a basis function. We call it a basis function because it is the fundamental element, or basis, of the model we will create and fit to the time series of the data. Furthermore, if we know what the shape of the distribution looks like in response to a very brief stimulus, we can predict what it should look like in response to stimuli of varying durations, as well as any combination of stimuli presented over time. We now turn to illustrations of each case.

The HRF for a Single Impulse Stimulus

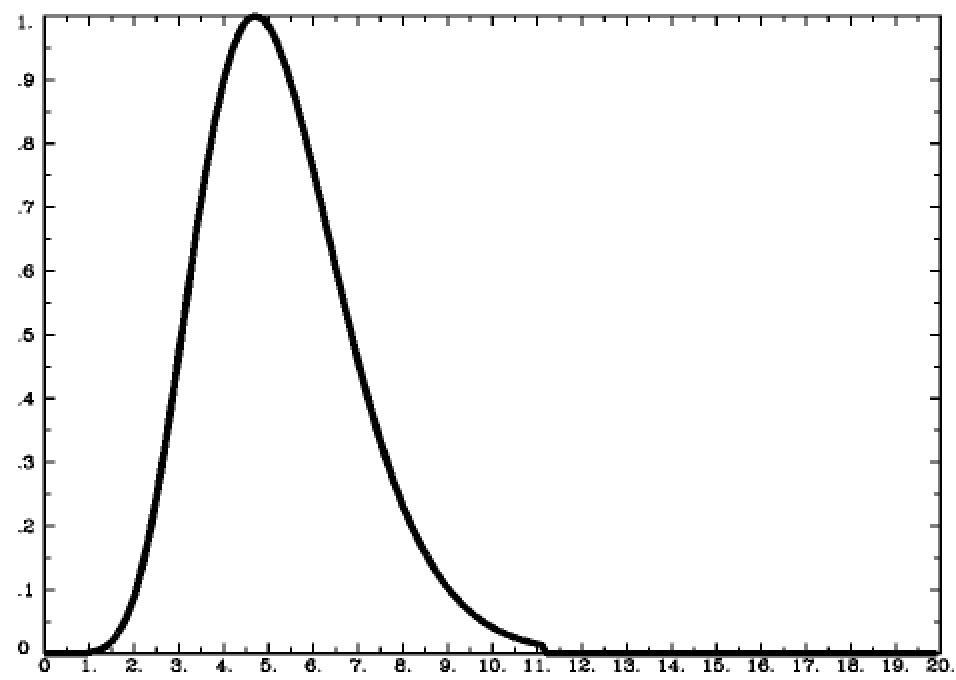

If the duration of a stimulus is very short, such as a snap of the fingers, we can say that it is an impulse stimulus - in other words, it has no duration. As you can see in the following figure, the shape of the BOLD signal looks like a typical Gamma Distribution, with a peak close to the beginning of the time axis (i.e., the x-axis) and a long tail to the right.

The HRF generated by a single impulse stimulus. In this figure, the stimulus occurs at timepoint 0 on the x-axis.

The HRF for a Single Boxcar Stimulus

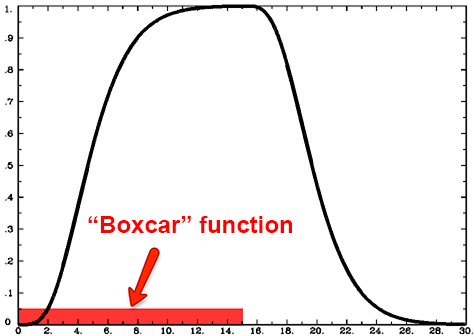

Although many studies use stimuli lasting only a second or less, some studies present stimuli for longer periods of time. For example, imagine that the subject looks at a flashing checkerboard for fifteen seconds. In this case the shape of the HRF will be more spread out with a sustained peak proportional to the duration of the stimulus, falling back to baseline only after the stimulus has ended. This stimulus is called a boxcar stimulus, because it looks like a boxcar on a train.

In this case the Gamma Distribution is convolved with the boxcar stimulus. Convolution is the averaging of two functions over time; as a result, the Gamma Distribution broadens as it is averaged with the boxcar stimulus, and returns to baseline when the stimulus is removed.

Note

In the Single Impulse case, the Gamma Distribution is also convolved with a stimulus. Since an impulse stimulus is infinitesimally small, it is represented as a vertical line on the time axis. This is why it is sometimes called a stick function.

Illustration of the HRF generated by a boxcar stimulus lasting for fifteen seconds. Note that the BOLD signal begins descending back to baseline around the fifteen-second mark.

What if the HRFs overlap?

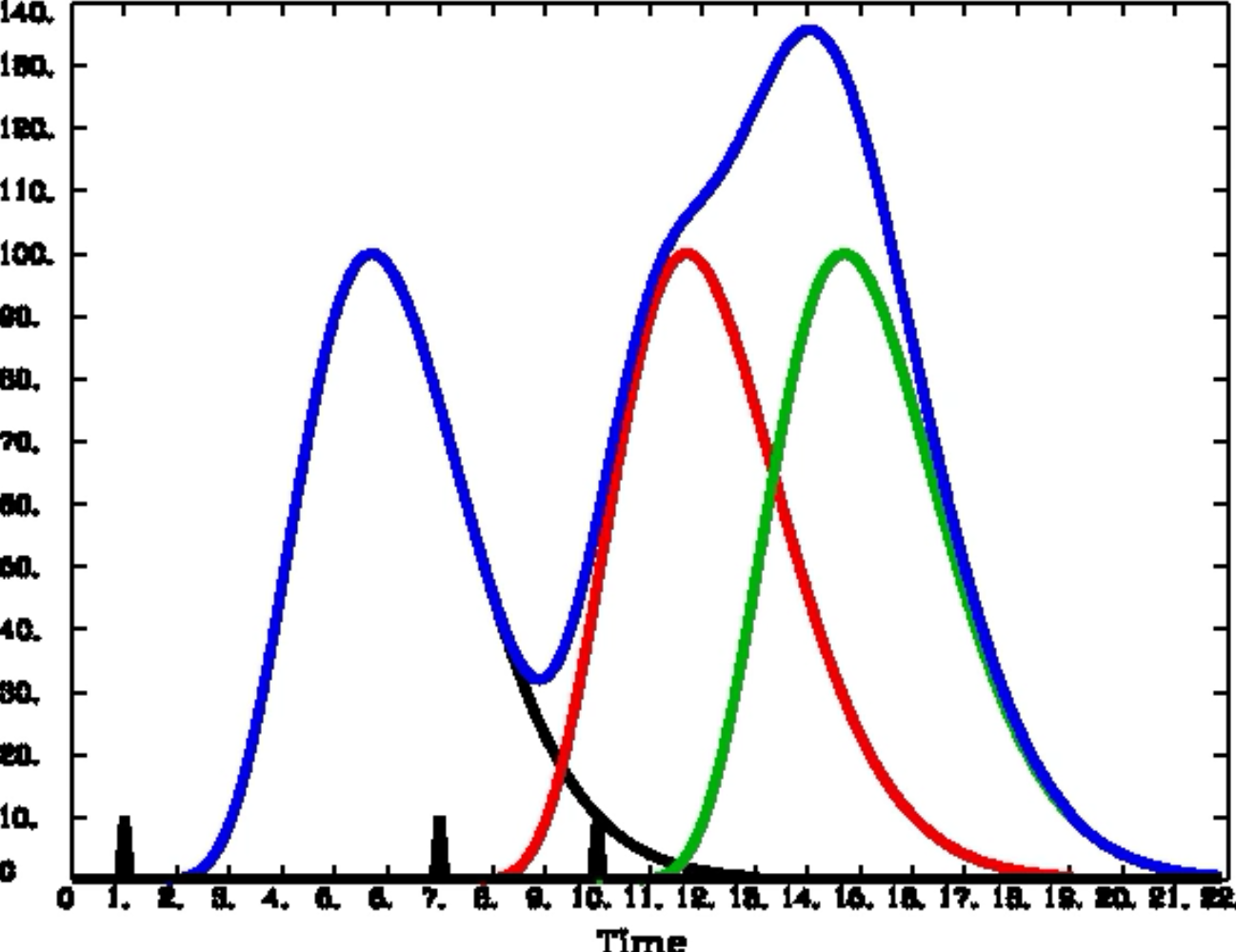

We have seen what the BOLD signal looks like after a stimulus is presented and how the HRF models the shape of that signal. But what happens if another stimulus is presented before the BOLD response for the previous stimulus has returned to baseline?

In that case, the individual HRFs are summed together. This creates a BOLD response that is a moving average of the individual HRFs, and the shape of the BOLD signal becomes more complex as more stimuli are presented close together.

Convolution of the HRFs for individual stimuli. The overall BOLD response (blue) is a moving average of the individual HRFs outlined in black, red, and green. The vertical black lines on the x-axis represent impulse stimuli. Figure created by Bob Cox of AFNI.

Putting it all together: Animations of each Case

To help you understand what you have just read, watch the following animation a couple of times. It will show how each of the cases described above unfolds over time, which will aid your comprehension.

Animations originally created by Bob Cox of AFNI.

Exercises

In this chapter the terms “hemodynamic response function” and “BOLD signal” were used to represent similar but distinct ideas. How would you define each of these terms in your own words?

Use this applet to practice convolving different shapes together. To replicate the convolution of the impulse function with the HRF, for example, set the input signal to “Dirac impulse” and the output signal to “custom,” and trace out the shape of a gamma function with your mouse. Also try setting the input signal to “Rectangle,” and try both widening and narrowing the shape.

Note

The concepts you have just learned are probably more difficult to understand than what you have learned previously in this course. Even if you don’t feel that you fully understand the HRF and convolution, go on with the rest of the module. After you have read the remaining chapters and have done the practical exercises, come back to this chapter and then see if it makes more sense.